Research Article - African Journal of Food Science and Technology ( 2024) Volume 15, Issue 2

Received: 07-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. AJFST-23-127167; , Pre QC No. AJFST-23-127167; , QC No. AJFST-23-127167; , Manuscript No. AJFST-23-127167; Published: 29-Feb-2024

This study assessed the handling and processing practices of 30 small-scale folded vermicelli processors in urban areas of Tanga City, Tanzania. The processors, found across various streets (ranging from 3.3% in Kwaminchi Street to 23.3% in Mabawa Street), exhibited diverse demographics, with 53.3% being owner-operators and 40% and 6.7% in laborer and supervisor roles, respectively. A significant portion (53.3%) had 1-3 years of experience, and 90% lacked formal training in pasta processing. Despite 73.3% possessing food manufacturing licenses, many were unfamiliar with legal requirements, lacking documentation and standardized processes, raising concerns about food safety. Raw materials were sourced locally, but 63.3% lacked storage facilities. Hygiene practices varied, with 43.3% undergoing periodic medical check-ups, and 70% using protective gear. Sun drying was the sole method employed, with 43.3% drying trays on rooftops. Packaging practices raised concerns, as 93.3% reused woven polypropylene bags, potentially impacting product quality. Only 6.7% had essential product labels. Awareness of aflatoxin and its health implications was lacking in 90% of the processors. Overall, the study highlighted gaps in awareness, training, and adherence to standards among small-scale vermicelli processors, posing potential risks to food safety and quality.

Folded Vermicelli; Small-Scale Processors; Handling Practices; Processing Practices; Tanga City; Tanzania.

Folded vermicelli is a traditional type of pasta which is commonly consumed in Tanga. The region is famous in pasta consumption, especially the folded vermicelli. It is believed that the Arab merchants introduced Italian pasta in various countries including Tanzania, especially the coastal regions (Claval & Jourdain-Annequin, 2017). Pasta consumption has become a tradition of the region and several processing units have been established. However, the consumption is relatively higher during the holy month of Ramadhan, when Muslims are fasting.

Although there are few large-scale pasta processing companies, the micro-scale units in Tanga are the producers of folded vermicelli. The production of folded vermicelli requires wheat flour and water as the main raw materials (Agarwal et al., 2019). However, the quality and safety of the final product depend on the raw materials used, processing techniques as well as the environmental hygiene of premises (Varzakas, 2016). Wheat flour is produced by large-scale companies with all measures to assure quality and safety. However, the micro-scale companies lack facilities and equipment to process and handle the product in a hygienic way. Inadequate processing conditions like personal hygiene and cleanliness of working surfaces are regarded as major routes of contamination (Carrasco et al., 2012; Holah, 2013; Jackson et al., 2008; Møretrø and Langsrud, 2017; Quinn et al., 2015).

Despite the fact that the production process of folded vermicelli is a thermal process involving steaming (pre-cooking) which kills most microorganisms, the drying process and handling practices of the finished products can pose a risk of cross contamination from both spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms. The processors use open sun drying method, whereby folded vermicelli in trays are placed on rooftops and/or on ground/floors for several days without any covering materials. They lack equipment and tools to assess the moisture content in dried products. Products may be packed while are not properly dried. Also packaging of dried vermicelli in used woven polypropylene bags, often without any cleaning intervention. These practices may create a potential route of products contamination with food safety hazards (Sousa, 2008). If folded vermicelli are dried for long time or packed while not well dried, there is a potential risk of growth of toxigenic fungi that may also produce mycotoxins. Many studies have reported on the factors related with aflatoxin contamination like handling of harvested crops, low levels of awareness and knowledge of producers/handlers and consumers of crops, educational and regulatory programs (Ayo et al., 2018; FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives, 2016; Kamala et al., 2016; Magembe et al., 2016; Ngoma et al., 2017; Waliyar et al., 2010). Despite the fact that folded vermicelli processors are small-scale, indeed they must ensure the safety of food products to prevent food borne diseases (Vasconcellos, 2003). Although some studies have been conducted to assess handling practices in fish (Kussaga et al., 2014) and dairy (Kussaga and Luning, 2015) processing companies little has been done in pasta processing companies. Therefore, this study intends to assess the handling and processing practices in folded vermicelli by small-scale processors in Tanga City. The findings from this study will be useful to food control authorities and other stakeholders to set up control strategies to small-scale processors in the country.

Study location

The study was conducted in Tanga City, in Tanga district (Figure 1). Tanga is one of eleven administrative districts of Tanga region in Tanzania. The district covers an area of 596.5 km2 of which includes the historic city of Tanga and the Port of Tanga. Geographically, Tanga is located on coordinates: 060 57” S 370 32” E. Tanga district is bordered to the north by Mkinga district, to the east by the Indian Ocean, to the south and west by Muheza district. It has an average temperature of 24.60C and 935 mm of rainfall per year, and the area is classified under tropical-climate. The district is the administrative and economic centre of the region. According to the 2022 National Census statistics; the city has a total population of approximately 245,182 people. The district is famous in production and consumption of pasta especially folded vermicelli. Nine streets from nine administrative wards in Tanga City were involved in this study.

Sampling design

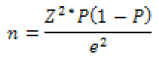

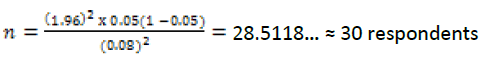

Multistage sampling design was implemented in this study (Acharya et al., 2013). In summary, three divisions (Chumbageni, Ngamiani Kaskazini and Ngamiani Kati) were purposefully selected among the four divisions of Tanga City. Nine administrative wards out of 27 wards, namely, Chumbageni, Duga, Mabawa, Ngamiani Kaskazini, Makorora, Msambweni, Central, Ngamiani Kati and Ngamiani Kusini were also purposefully selected. The wards selected were those with at least one folded vermicelli processing company. Then, all the streets with the folded vermicelli processors were taken from each of the chosen wards, as indicated in the sampling plan (Figure 2). Finally, 30 small-scale processors were selected from each street (n=30).

Where; n = the required sample size, Z = the level of statistically significant at 95% confidence interval = 1.96, P = the percentage occurrence of a state or condition = 5%, and e = the percentage maximum marginal error required = ±8% for this study.

Survey of small-scale folded vermicelli processor’s awareness on handling and processing practices

Face-to-face interviews were conducted to assess the handling and processing practices through nine streets. Information was collected from each respondent, a total of 30 respondents were interviewed from 30 small-scale folded vermicelli processors using a semi-structured questionnaire and the observation checklists. Information was collected from each company. All processing units were involved in this research study.

Statistical data analysis

Data from the questionnaires were processed by editing, coding and analyzing by using a Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS Version 25, 2017). Descriptive statistic was employed. The data were then presented as frequencies and percentages.

Demographic characteristics of the processors

The majority (70%) of respondents were male, indicating a gender disparity in the industry (Table 1). This could be attributed to the nature of the business and associated activities (lifting, mixing/molding), which favoured masculine. These findings contradict those of earlier studies where Hassan and Fweja (2020) report that 67.5% of the food street vendors are females and 32.5% are males. Likewise, the findings from the study by Rabia et al. (2017) reveal that 74.8% of the processors are males and 25.2% are females, and Masunzu (2017) reports that 80% are males and 20% are females. In terms of age distribution, a significant portion of processors fell in the 31-40 age group (43.3%), followed by those above 50 (26.7%). This data indicated a diverse age group within the processing industry, with a considerable number of more experienced individuals. With regards to education level, the majority of processors had secondary (40%) and primary school (43.3%) education. These findings agree with Ali et al. (2023), who reveal that the majority (61.5%) of respondents have accomplished secondary school. However, they contrast with the findings reported by Chijoriga (2017), which highlight that 64% of SMEs food processors have vocational education in food processing. It was also observed that the businesses were predominantly dominated by owners (53.3%). Small-scale folded vermicelli processing seemed to be mostly ran by the owners themselves, with few positions for labourers (40%) and supervisors (6.7%). This could impact the overall management and quality control within the businesses. The majority (53.3%) of processors had relatively limited (1-3 years) working experience in the industry. However, they were likely in the learning phase, refining their skills and optimizing their production methods. Those with 4-6 years (23.3%) of experience likely possessed a more advanced understanding of the production processes. They had encountered various challenges and learned how to overcome them, contributing to increased efficiency. However, processors with more than 7 years (16.7%) of experience were likely seasoned experts in the field. They had a deep understanding of the intricacies of producing folded vermicelli, which could contribute to higher product quality and efficiency. Experience adds value to the work and can determine small microenterprises (SMEs) ability to upgrade (Loewe et al., 2013). A relatively small portion (10%) of processors had attended a training course, specifically a seminar on pasta production held at Zanzibar for one week. They had acquired additional knowledge and skills relevant to the production of folded vermicelli. Those who hadn’t attended training courses (90%) relied solely on their practical experience. The lack of training attendance is a significant concern, as it may limit the processor's knowledge about best practices, quality control, and safety standards in folded vermicelli production. Challenges faced by small food companies in implementing Food Safety Management Systems, as reported by Osei and Anfu (2019), stem from insufficient knowledge about food safety processes, alongside issues related to infrastructure and proper handling of food equipment in processing firms. All owners and employees working in food premises, including temporary employees, should be trained on the basics of food safety principles and practices required to prevent contamination and cross-contamination of foods (Duan et al., 2011; Dudeja and Singh, 2017; Ebert, 2017).

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 21 | 70.0 |

| Female | 9 | 30.0 | |

| Age (in years) | Below 18 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 18 – 30 | 5 | 16.7 | |

| 31 – 40 | 13 | 43.3 | |

| 41 – 50 | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Above 50 | 8 | 26.7 | |

| Education level | Non formal | 3 | 10.0 |

| Primary | 13 | 43.3 | |

| Secondary | 12 | 40.0 | |

| Vocational Training | 2 | 6.7 | |

| University | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Work position | Owner | 16 | 53.3 |

| Manager | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Quality Assurance | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Supervisor | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Labourer | 12 | 40.0 | |

| Work experience (in years) | Below 1 | 2 | 6.7 |

| 1 – 3 | 16 | 53.3 | |

| 4 – 6 | 7 | 23.3 | |

| ˃ 7 | 5 | 16.7 | |

| Training course | Yes | 3 | 10.0 |

| No | 27 | 90.0 | |

Characteristics of the company

The distribution of processors across different streets in the urban areas of Tanga City was varied. The proportions of processors in each street were Mabawa (23.3%), Msambweni (16.7%), Central (13.3%), and Azimio (13.3%) (Table 2). This variation could have been due to easy accessibility to resources, market demand, and/or historical factors. The majority (73.3%) of processors had a food manufacturing license issued by the Municipal Council or TBS (formerly, the Tanzania Food and Drugs Authority). This suggested that the majority of processors were aware of the importance of obtaining the necessary licenses to operate legally. It was crucial for ensuring the safety and quality of the food products they produced. On the other hand, none of the processors had registered their companies, indicating that all were operating informally. This is in agreement with a study by Ruteri (2009) revealed that micro and small food processors in Tanzania operate in the informal sector, employing labour-intensive methods and utilizing inadequate technologies.

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location (Streets) | Magomeni | 2 | 6.7 |

| Mabawa | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Azimio | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Swahili | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Msikiti | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Makorora Kati | 3 | 10.0 | |

| Msambweni | 5 | 16.7 | |

| Central | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Kwaminchi | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Company registration | Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |

| Food manufacturing license | Yes | 22 | 73.3 |

| No | 8 | 26.7 | |

| Number of employees | Below 10 | 21 | 70.0 |

| 10 – 49 | 9 | 30.0 | |

| Above 50 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Company inspection | Yes | 22 | 73.3 |

| No | 8 | 26.7 | |

| Inspection frequency (in year) | Once | 0 | 0.0 |

| Twice | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Three times | 11 | 36.7 | |

| Over three times | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Production frequency per week | 7 days | 3 | 10.0 |

| 6 days | 6 | 20.0 | |

| 3 days | 21 | 70.0 | |

| Quantity produced per day (in bags) | 0 – 30 | 21 | 70.0 |

| 31 – 100 | 9 | 30.0 | |

In addition, seventy percent of the processors had fewer than 10 employees, while 30% had between 10 and 49 employees (Table 2). The number of employees depended on the scale of production and the available resources, indicating that they were truly categorized as small-scale entrepreneurs. A significant portion of the companies (73.3%) were inspected; 36.7% of those inspected were inspected three times a year. Company inspections were critical for quality control and ensuring compliance with food safety standards. TBS and government health officers inspected the processor’s companies on a number of activities, including the general cleanliness of premises, facilities and personal hygiene, building maintenance and sewerage repair, routine medical check-up, wearing of protective gears and proper uniforms, and business licenses. Processors undergoing inspections have a better understanding of the importance of quality and safety standards in food production (Okpala and Korzeniowska, 2023). The production frequency also varied; the majority (70%) of processors had a frequency of three days per week, while the rest had 6 (20%) to 7 (10%) days frequency (Table 2). The production frequency could be influenced by factors such as market demand, processing capacity, and product shelf life. Seventy percent of processors produced 1-30 bags per day, while the rest (30%) had a daily production capacity of 31-100 bags. The daily production capacity depended on the size of the processing equipment, workforce, and market demands. Only one of the processors had a large production quantity of about 98 bags per day. This was because they had a self-sufficient company and equipment, enough workforce, and high market demand.

Handling of raw materials

The study showed that all processors (100%) purchased their raw materials from the local markets, and they were considered quality (90%) as a purchased factor (Table 3). Sourcing raw materials from local markets was a common practice for small-scale processors in Tanga City, as it provided convenience and access to a variety of materials. Visual checks can only identify visible contaminants, such as dirt, insects, or foreign objects that are large enough to be seen with the naked eye. On the other side, many harmful contaminants, such as bacteria, viruses, chemical residues, and allergens, are not visible and cannot be detected through visual inspection alone (Tolmacheva et al., 2019). Prioritizing quality over price in raw material selection was a positive practice in food production, as quality raw materials were essential for producing safe and high-quality food products. Price-conscious decisions may have been a result of cost constraints but could sometimes compromise quality.

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are raw materials purchased from local markets? | Yes | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Factors considered in purchasing of raw materials | Price | 3 | 10.0 |

| Quality | 27 | 90.0 | |

| Do you have store for raw materials? | Yes | 11 | 36.7 |

| No | 19 | 63.3 | |

| Is there any spoilage problem of stored raw materials? | Yes | 5 | 16.7 |

| No | 25 | 83.3 | |

| Possible sources of spoilage | Moisture | 3 | 10.0 |

| Moulds | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Insects/rodent | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Is the TUWSSA taken as the source of water (tap water) used? | Yes | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 |

Less than half (36.7%) of processors had stores for raw materials, while 63.3% did not (Table 3). For those who did not have storage facilities, they stored raw materials either in their homes or at the processing areas/rooms. Storage facilities protected raw materials from spoilage and maintained their quality. The absence of storage facilities could have been due to space and financial constraints or a lack of awareness of the benefits of proper storage. Ensuring the quality of agricultural raw materials necessitates well-designed storage facilities, which many companies find it challenging to purchase and set up due to financial constraints (Georgiadis et al., 2005). The data showed that few processors (16.7%) reported spoilage problems, where moisture (10%) was identified as a frequently source of spoilage. Spoilage could occur due to various factors, including inadequate storage, exposure to moisture, and pests. The percentage of reported spoilage suggested that there was room for improvement in handling and storing raw materials to reduce losses. The food hygiene practices require dedicated food storage facilities to provide an environment that minimizes the impacts of food deterioration agents (Kamboj et al., 2020). All processors used tap water from Tanga Urban Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (TUWSSA) as their source of water (Table 3). Using tap water from a regulated source like TUWSSA was a good practice as it ensured consistent quality and safety. Generally, the deliberate or accidental food contamination due to inappropriate handling of food causes a potential threat to consumer’s health (Annor and Baiden, 2011).

Hygiene and sanitation practices

This study showed that 43.3% of processors underwent periodic medical check-ups, while 56.7% did not (Table 4), possibly due to cost constraints or a lack of awareness regarding their importance. Employees who are suffering from infectious diseases can inadvertently contaminate the food they handle, either through direct contact or by contaminating surfaces, utensils, and equipment. This can lead to the spread of pathogens to the final food product, increasing the risk of foodborne illnesses among consumers (Djukic et al., 2016). Only 20% had a changing or dressing room, while 80% did not. Having a designated area for changing and dressing rooms helped prevent contamination of work clothes and maintained hygiene. The absence of such facilities may have resulted from space limitations or a lack of awareness about their importance. About 70% wore protective gear, while 30% did not. Wearing protective gear, such as aprons, gloves and hairnets, is important to prevent contamination of the product as they act as a barrier between workers and the food they handle, reducing the chances of transferring contaminants from the worker’s clothing, hair, or skin to the food and helps maintain high standards of personal hygiene among food processing workers (Todd et al., 2010). More than half (60%) of processors had hand washing facilities, while 40% did not. Hand washing facilities were essential to prevent the spread of pathogens. The absence of such facilities may have been due to infrastructure limitations or a lack of awareness regarding the importance of hand hygiene. In terms of timing, hand washing was reported to occur after visiting toilets (46.7%), after shaking hands with others (16.7%), after blowing the nose (23.3%), and before starting processing (13.3%). Failing to practice those could have significant implications for food safety. Proper hand washing at these times aligned with GHP, helping to reduce the risk of contamination during food processing. They also used coconut or cooking oil for cleaning (oiling) machines (Table 4). Using edible oils like coconut or cooking oil for cleaning machines was a common practice that helped prevent rust and made machine parts slippery, considered safe. Regular cleaning of machines, equipment, and utensils was essential to prevent the build-up of contaminants and ensure food safety and quality.

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is the periodical medical check-up conducted? | Yes | 13 | 43.3 |

| No | 17 | 56.7 | |

| Do you have changing/dressing room? | Yes | 6 | 20.0 |

| No | 24 | 80.0 | |

| Do you wear the protective gears? | Yes | 21 | 70.0 |

| No | 9 | 30.0 | |

| Do you have toilet(s)? | Yes | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Do you have hand washing facilities? | Yes | 18 | 60.0 |

| No | 12 | 40.0 | |

| At what time do you wash your hands? | After visiting toilets | 14 | 46.7 |

| After hand shaking with others | 5 | 16.7 | |

| After blowing nose | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Before starting processing | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Is unnecessary foot traffic not allowed in processing areas? | Yes | 3 | 10.0 |

| No | 27 | 90.0 | |

| Do you clean the processing machines? | Yes | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Is coconut/cooking oil used for cleaning machines? | Yes | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Cleaning of equipment and utensils | Normal portable water | 30 | 100.0 |

| Hot water | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Cleaning of drying facilities | Sweeping with hand broom, brushing and mopping | 4 | 13.3 |

| Sweeping with hand broom and brushing | 26 | 86.7 | |

| Do you have any other water treatment in company? | Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |

| How do you dispose your waste? | In communal collection Municipal point | 26 | 86.7 |

| Burn at home waste pit | 4 | 13.3 |

None of the processors implemented other water treatment methods. This could have been because they relied on the quality of tap water from a regulated source. Regarding waste disposal, 86.7% of processors disposed of their waste in communal collection municipal points, while 13.3% burned their waste in home waste pits. Proper waste disposal is crucial for maintaining cleanliness and preventing environmental contamination (Hossain et al., 2011). This indicates that all processors made an effort to dispose of their waste and maintain a clean and hygienic environment to prevent food contamination and the spread of foodborne illnesses.

Manufacturing process of folded vermicelli

Nowadays, pasta is processed by continuous, high-capacity extruders that operate on the auger extrusion principle, combining kneading and extrusion in a single operation (Bashir, 2012). The production of folded vermicelli by small-scale processors in Tanga City involved the following steps:

Mixing and kneading: Wheat flour and water were mixed in precise proportions in a mixer to form a pasta dough. The dough was then kneaded with water at a temperature of 20 to 30°C.

Extrusion: Once the stiff dough was uniformly mixed and formed, it was fed into a sheeter and former machine to create dough plates. These plates were then passed through a die machine under high pressure to produce a wide variety of vermicelli, with the shape and size of the die adjusted accordingly.

Steaming and folding: The sized and shaped vermicelli were placed into pasteurizer tanks/vessels for thermal treatment, typically for 1 to 1½ hours to reach a pre-cooking condition. Most processors used gas combustion to boil water for steam production, although one processor used crude oil combustion, which posed a serious environmental issue with smoke disposal. After steaming, the partially cooked vermicelli were folded into their final shapes (folded vermicelli) and prepared for the drying process. Thermal treatment not only ensures safety by reducing microbial populations and altering the pasta structure through water activity reduction, but it also leads to unwanted modifications (Giannetti et al., 2021).

Drying: Special attention is given to the final step of the pasta-making process: the drying step. It is well-known that the drying process gives dry pasta its desired physical and chemical stability and allows it to have a longer shelf life (Bresciani et al., 2022). The drying time is also crucial, as over-drying can cause the pasta to break down, while drying too slowly increases the risk of spoilage (Varzakas, 2016).

The formed folded vermicelli were placed on drying trays and then left on rooftops or on the floor/ground for two days, which was sufficient drying time if there was enough sunlight.

Weighing and packaging: The dried folded vermicelli was weighed according to the processor's decision and customer requirements, and then packaged in either new or used woven polypropylene (PP) bags. The packaged folded vermicelli was then ready for sale.

Processing and drying practices of folded vermicelli

All processors (100%) were engaged in seasonal and batch production (Table 5), with a focus on the holy month of Ramadhan due to increased customer demand. However, a few of them continued producing even after the holy month of Ramadhan when they received orders from their customers. Also, all processors used a semi-automated system. In this case, some tasks were performed by human operators, while others were completed by machines. This practice was commonly used in small-scale food processing due to its cost-effectiveness and suitability for lower production volumes. In small-scale folded vermicelli enterprises, product quality fluctuated due to insufficient quality control facilities, a lack of awareness about their importance, and substandard manufacturing practices.

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seasonal production | Yes | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Processing machines/work used | Automated machines/work | 0 | 0.0 |

| Semi-automated machines/work | 30 | 100.0 | |

| Drying method used | Sun drying | 30 | 100.0 |

| Oven drying (oven charcoal dryer) | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Cabinet dryer | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Where do you put it when dries on the sun? | On roof tops | 26 | 86.7 |

| On ground/floor | 0 | 0.0 | |

| On roof tops and on ground/floor | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Do you cover folded vermicelli when drying? | Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |

| Drying period | Two days | 30 | 100.0 |

| Three days | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Dryness identification | By inserting a finger inside a folded vermicelli | 30 | 100.0 |

| By breaking a folded vermicelli | 0 | 0.0 | |

| By using a moisture meter | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Challenges experienced in drying process | Lack of cover-materials when drying | 5 | 16.7 |

| Hard work to put trays on roof tops | 13 | 43.3 | |

| Lack of dryer | 3 | 10.0 | |

| Tedious work in monitoring activity | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Expensive when use of oven charcoal drier | 2 | 6.7 |

All processors used sun drying as the primary method for drying folded vermicelli, and none of them used cabinet dryers or oven drying. The current study conducted by Sasongko et al. (2021) in Indonesia aligns with this study, revealing that the majority of vermicelli drying in small to medium enterprises relies on sunlight. This method's drawback lies in its dependence on weather conditions, impacting both the continuity of drying and the quality of the vermicelli (Sasongko et al., 2021). The majority (86.7%) of processors placed folded vermicelli on rooftops, while 13.3% used both rooftops and the ground/floor for drying activity. Placing it on rooftops took advantage of direct sunlight and good airflow, aiding in the drying process. The choice of location depended on the available space and infrastructure, as some processors did not have enough space for such activity. None of the processors covered the folded vermicelli while drying. Covering folded vermicelli during sun drying was not a common practice for processors because they could not afford it, and they believed it may trap moisture and hinder the drying process. Open air exposure was preferred for effective drying, but it also posed a risk of contamination from dust, bird droppings, and other foreign matters. The findings showed that all processors reported a drying period of two days, which could vary depending on factors such as weather conditions. In the event of unfavourable weather conditions, such as rain, an oven charcoal dryer was used for one day after two days of exposure to sunlight, although it was an expensive method. All processors identified dryness physically by inserting a finger into folded vermicelli (Table 5), which was a key factor in verifying the quality of the product by assessing its moisture content. None of them used a moisture meter. Manual inspection by touch is a practical and effective method commonly used in food processing to determine the dryness of pasta especially folded vermicelli (Zambrano et al., 2019).

The study indicated that the processors faced several challenges (Table 5). The most challenging was the hard work to put trays on rooftops (43.3%) and remove them after drying or in rainy conditions. These challenges reflected the limitations and constraints faced by small-scale processors, including a lack of resources, infrastructure, and equipment access, which could impact the drying process. Understanding these practices and challenges was crucial for improving the efficiency and quality of folded vermicelli production in small-scale settings.

Quality control of the end products

Despite the fact that the majority of processors had years of experience, none of the processors was familiar with the specific requirements set by the TBS (Table 6). Instead, they relied on common sense to judge the quality of end products, such as folded vermicelli, which could be risky in terms of food safety. None of the processors reported having working instructions, operating procedures, and pasta processing flow chart in place. Instead, they relied on habits. This absence of formal documentation may have indicated a lack of consistency and quality control, also posing a risk for cross-contamination. Only 23.3% of processors maintained medical examination records for their employees, while the majority (76.7%) did not. The low percentage may have been due to factors such as the cost of medical examinations and a lack of awareness of health and safety requirements in the workplace. Also, none of the processors reported having records for cleaning and disinfection schedules. This suggested a potential lack of formalized and systematic cleaning and sanitation practices within their facilities, which could pose a hygiene risk and may result from limited awareness of best practices or a lack of resources for record-keeping.

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you meet specific requirements as per TBS? | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |||

| Do you have working instructions and operating procedures? | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |||

| Do you have pasta processing flow chart? | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |||

| Do you have medical examination records? | Yes | 7 | 23.3 | ||

| No | 23 | 76.7 | |||

| Do you have cleaning and disinfestation schedule records? | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |||

| Product safety assurance: | |||||

| a. Using good raw materials | Yes | 30 | 100.0 | ||

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| b. Conducting good hygienic practices-GHP | Yes | 8 | 26.7 | ||

| No | 22 | 73.3 | |||

| c. Conducting good manufacturing practices-GMP | Yes | 6 | 20.0 | ||

| No | 24 | 80.0 | |||

| d. Proper product packaging | Yes | 2 | 6.7 | ||

| No | 28 | 93.3 | |||

| e. Proper product storage | Yes | 13 | 43.3 | ||

| No | 17 | 56.7 | |||

Product safety assurance controls the quality of raw materials and critical processing elements. It guarantees that ingredients have quality, and there are processes in place that are validated and monitored concerning food safety (Batt, 2016). The study illustrated that all processors claimed to use good raw materials (Table 6), indicating a commitment to ingredient quality. Few of them conducted good hygienic practices (GHP) (26.7%) and good manufacturing practices (GMP) (20%), indicating a potential area for improvement in terms of the overall manufacturing process that ensures product consistency, quality, and safety. Good Hygienic Practices (GHPs) are the procedures and practices undertaken using best practice principles to prevent contamination during the production process (FAO and WHO, 2023). Eight percent of processors failed to comply with GMP that could lead to variations in product quality and potential safety risks. Proper product packaging and storage were also areas that needed improvement. A small percent (6.7%) reported having good product packaging material (Table 6), packaged in new woven polypropylene bags, but without a coating of excellent barrier materials (Poly-Vinylidene Chloride~PVDC). The majority (93.3%) reused woven polypropylene bags that were previously used to pack wheat flours, resulting in possible product contamination and a potential impact on its quality. This implies that most respondents may not prioritize packaging as a safety measure. Additionally, approximately 43.3% reported having proper product storage, where their packaged bags were stored in a dry place under wooden pallets to avoid moisture uptake. Storing products under appropriate conditions helped maintain their quality and ensured that they met safety standards. The remaining 56.7% did not. This indicated that a significant proportion was less aware of the importance of storing products appropriately. Generally, using good raw materials is a fundamental aspect of food safety. However, the lack of good hygienic and manufacturing practices and proper product packaging could result in contamination and spoilage. The absence of proper storage could also lead to product degradation, especially in tropical climatic conditions areas like Tanzania.

Packaging and labeling information of the final products

The study indicated that all processors were engaged in production packaging (Table 7), which was a positive practice. None of the processors used polyethylene (PE) bags, while the majority (93.3%) reused woven polypropylene (PP) bags that have chances for contamination and easy brittleness of the packaged product when handling these bags. Azahar et al. (2004) validate these findings, observing that many Malay SMEs in Malacca continue to manufacture products utilizing inexpensive packaging materials, resulting in unappealing packaging and labeling. Only 6.7% used new woven polypropylene (PP) bags with a label. Woven polypropylene (PP) bags, whether new or used, are commonly used in food packaging due to their durability and low cost. Generally, pasta products should be packaged in food-grade packaging material to safeguard the hygienic, nutritional, technological, and organoleptic qualities of the products. The weight of packaged bags varied, with 20% using 12.5 kg bags, 40% using 12 kg bags, 16.7% using 11 kg bags, and 23.3% using 10 kg bags (Table 7). The choice of bag weight can be influenced by market demand and consumer preferences. The majority (76.7%) of processors sealed the bags by machines, while 23.3% did not. Sealing the bags is important to prevent air, moisture, and other external contaminants from entering, which can affect the product's quality (Ilhan et al., 2021). It is also advantageous to prevent tampering, fraud, and adulteration of the packaged products. Only 6.7% of processors used product labels, while the majority (93.3%) did not. Product labels provide essential information to consumers, including branding, product details, and instructions. The low percentage using labels might be due to cost constraints or a lack of awareness about labeling requirements. Additionally, 6.7% of processors included production and expiry dates on their packaging, while the majority (93.3%) did not. Providing production and expiry dates is crucial for food safety and consumer information. It was also observed that only one processor (3.3%) had a batch number, while the majority (96.7%) did not have. Batch numbers help in tracking and tracing products in case of recalls (Fritz and Schiefer, 2009). Additionally, a small number of processors (6.7%) included the manufacturer's name and contact address on their packaging, while the majority (93.3%) did not include it. Including the manufacturer's information is important for transparency and accountability. Failure to indicate other required information could result in the misuse or improper storage of those products. Also, the failure to indicate a list of ingredients could pose a risk to the health of allergic individuals (Messer et al., 2017). These practices were crucial for ensuring product safety, consumer trust, and regulatory compliance.

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product packaging | Yes | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Type of packaging materials used | Polyethylene (PE) bags | 0 | 0.0 |

| New woven polypropylene (PP) bags | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Used woven polypropylene (PP) bags | 28 | 93.3 | |

| Weight of packaged bag (in kg) | 12.5 | 6 | 20.0 |

| 12 | 12 | .40.0 | |

| 11 | 5 | 16.7 | |

| 10 | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Sealing of the packaged bags | Yes | 23 | 76.7 |

| No | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Product label | Yes | 2 | 6.7 |

| No | 28 | 93.3 | |

| Production and expiry date | Yes | 2 | 6.7 |

| No | 28 | 93.3 | |

| Batch number | Yes | 1 | 3.3 |

| No | 29 | 96.7 | |

| Manufacture name and contact address | Yes | 2 | 6.7 |

| No | 28 | 93.3 |

Storage of final products and marketing information

Approximately 43.3% of processors had storage facilities, while more than half (56.7%) did not (Table 8), either because they stored their products at home or at the processing areas/rooms. Having storage facilities is crucial for preserving the quality and safety of food products. Limited storage forces processors to stack products, creating poor ventilation and a dusty, uncomfortable work environment. This can impact the health of workers, emphasizing the need for improved storage facilities (Ruteri, 2009). Half (50%) of processors stored their products for less than 1 month, 30% for 1 to 3 months, and 20% for 4 to 6 months. None stored for more than 6 months. Shorter storage durations help to maintain product quality and safety. It was noted that some of the processors had no proper storage facilities in place. A smaller number (16.7%) of processors reported spoilage problems, while the majority (83.3%) did not. Spoilage can occur due to factors such as inadequate storage conditions and the presence of pests (Atanda et al., 2011). The majority not reporting spoilage suggested that they effectively managed their storage facilities and sold their products in a timely manner. Of those reporting spoilage, 10% attributed it to moulds, and 6.7% to insects/rodents. Moulds and pests can thrive in inadequate storage conditions. In terms of interaction with customers, the findings showed that the majority (63.3%) of processor’s products were sold to retailers and individuals. Retailers and individuals are the primary customers due to the small-scale nature of the processors. Less than half (46.7%) of processors received different complaints from customers. The complaints varied among the customers, with the majority (26.7%) complaining about easy breakage/brittleness of the products. These complaints are consistent with common quality issues in food processing. Only a few processors (20%) experienced customer returns, while the majority (80%) did not (Table 8), as they maintained product quality to meet customer expectations. In terms of actions for returned products, 6.7% of processors received and destroyed, and 13.3% use/sold as animal/chicken feed. Proper handling of returned products is essential for food safety. Destroying or repurposing them as animal feed can prevent the returned products from re-entering the market. Proper storage practices and effective handling of customer complaints and returns are essential for ensuring product quality and safety.

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have store for final products? | Yes | 13 | 43.3 |

| No | 17 | 56.7 | |

| Products stored until next season | Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 30 | 100.0 | |

| Storage duration (in month) | Less than 1 | 15 | 50.0 |

| 1 – 3 | 9 | 30.0 | |

| 4 – 6 | 6 | 20.0 | |

| More than 6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Spoilage problems of stored products | Yes | 5 | 16.7 |

| No | 25 | 83.3 | |

| Possible sources of spoilage | Moulds | 3 | 10.0 |

| Insects/rodents | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Customers | Wholesalers, retailers and individual | 8 | 26.7 |

| Wholesalers and retailers | 3 | 10.0 | |

| Retailers and individual | 19 | 63.3 | |

| Do you receive any complaint from customers? | Yes | 14 | 46.7 |

| No | 16 | 53.3 | |

| What kind of complaint? | Inadequate dried products | 2 | 6.7 |

| Easy breakage/brittle products | 8 | 26.7 | |

| Foreign matter contamination | 3 | 10.0 | |

| Discoloration of the products | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Have customers return products? | Yes | 6 | 20.0 |

| No | 24 | 80.0 | |

| What you do for returned products? | Receive and destroy it | 2 | 6.7 |

| Use/sell as animal/chicken feed | 4 | 13.3 |

Processor’s awareness on aflatoxin

The majority of respondents (90%) were not aware that mould growth in food can result in aflatoxins. As for those who were aware (10%), it was mainly through mass media and hospital (Table 9). Consequently, only one who attended the training managed identify the disease caused by aflatoxin. The lack of awareness among the majority may be due to limited education and training. Similarly, a study conducted by Kimario et al. (2022) in Chamwino Dodoma, Tanzania, reported that there was very low awareness on mycotoxins among smallholder farmers. More than half (53.3%) of smallholder famers did not know about fungi (Kimario et al., 2022). Also, a current study conducted by Kitigwa et al. (2023) indicated a general low aflatoxin awareness (23.2%) among smallholder dairy farmers from three agroecological zones (Hai, Mpwapwa, and Serengeti districts) in Tanzania. Also, in Tanzania, especially among smallholder farmers, there is currently a notable lack of widespread awareness regarding the risks associated with aflatoxins, encompassing both health and trade aspects stakeholders (Massomo, 2020). Similar findings on the level of aflatoxin awareness were reported in Rwanda (10%) (Nishimwe et al., 2019), 21% in Uganda (Nakavuma et al., 2020), and 25% in Tanzania (Ayo et al., 2018). In contrast, from this study, the level of aflatoxin awareness was relatively higher in Kenya (55%) (Walke et al., 2014). For the one who identified the disease caused by aflatoxin, only 3.3% of processors learned about toxins and aflatoxin through colleagues (within and/or outside the company), 3.3% through mass media (television, radio, and/or newspapers), and another one (3.3%) through the hospital informed by doctors/nurses, while the majority had not heard about them (Table 9). Likewise, a study conducted in Tanzania reported that few smallholder dairy farmers who at least heard the word aflatoxin got most of the information from radios/televisions (47.7%) and extension officers (16.9%), but the majority were not aware (Kitigwa et al., 2023). Similarly, Ayo et al. (2018) observed that mass media, village officers, and extension officers were the major routes of information transfer about aflatoxins to smallholder dairy farmers and other stakeholders in Tanzania. The limited exposure to mass media and healthcare sources highlights the need for more structured education and training programs. Some studies conducted in Tanzania and other parts of the world publicized that education plays a larger role in creating awareness and reducing aflatoxins contamination of foods (Ayo et al., 2018; Jolly et al., 2009).

| Variable | Respondent/categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you know mould cause toxin in food? | Yes | 3 | 10.0 |

| No | 27 | 90.0 | |

| If yes, which toxin? | Aflatoxin | 3 | 10.0 |

| How did you know? | Mass media | 1 | 3.3 |

| Hospital | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Colleague | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Which condition can result to mould growth? | Inadequate drying | 10 | 33.3 |

| Moisture up-take | 5 | 16.7 | |

| Inadequate cleaned storage room | 2 | 6.7 | |

| I don’t know | 13 | 43.3 | |

| Do you know that aflatoxin can affect human health? | Yes | 3 | 10.0 |

| No | 27 | 90.0 | |

| Which health effect? | Cancer | 1 | 3.3 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Nausea | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0.0 |

The findings reported that about 10% of processors were aware that aflatoxin can affect human health, while the majority (90%) were not aware of aflatoxin and its potential health effects (Table 9). A different study conducted in Kilosa, Tanzania, found that 66.7% of the respondents were not aware of health hazards caused by mycotoxins (Magembe et al., 2016). Also, different studies conducted to assess aflatoxin awareness; Matumba et al. (2015) reported a lack of awareness on health effects caused by mould and mycotoxins among smallholder farmers in Malawi. Kimario et al. (2022) reported that 81.1% of respondents were not aware that fungi contamination may cause health problems in Chamwino Dodoma, Tanzania. The limited knowledge of the aflatoxin’s human health effects highlights the importance of raising awareness about aflatoxin-related health risks. Generally, the majorities of small-scale processors in developing countries, including Tanzania, are less aware of aflatoxin contamination and the associated health impacts that might arise after consuming aflatoxin-contaminated foods (Unnevehr and Grace, 2013). The structured education and training programs of aflatoxin awareness were needed for small-scale processors of folded vermicelli to address this knowledge gap.

Pasta processing industry in the country is dominated by micro-scale companies with limited knowledge, training and proper handling of the finished products. The lack of training and knowledge translation, coupled with limited awareness of regulatory standards, poses substantial risks to hygiene and safety. Poor hygienic and manufacturing practices, inadequate storage facilities, and the re-use of used packaging materials which can be contagious can compromise the quality of processed folded vermicelli. Addressing these critical issues is paramount for the industry's ability to upgrade and maintain safety standards, emphasizing the urgent need for targeted interventions, training programs, and regulatory enforcement to enhance hygiene practices and ensure the production of safe and high-quality folded vermicelli products. Therefore training of food processors and close monitoring of the industry is of paramount importance if quality and safety of vermicelli are to be guaranteed.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jamal B. Kussaga and Dr. David N. Chaula for their valuable input in this article. This research was funded by the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA).

Acharya AS, Prakash A, Saxena P, Nigam A (2013). Sampling: Why and how of it. India J Med Specialities. 4(2): 330-333.

Agarwal S, Chauhan ES (2019). Extrusion processing: The effect on nutrients and based products. J Pharm Innov. 8(4): 464-470.

Ali AH, Kilima BM, Wenaty A (2023). assessment of food safety knowledge, hygienic practices and microbiological quality of halwa produced in urban west region, Zanzibar. European J Nutr Food Saf.15 (12):117-129.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Annor GA, Baiden EA (2011). evaluation of food hygiene knowledge attitudes and practices of food handlers in food businesses in accra, ghana. Nutr Food Sci. 02(08):830–836.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Atanda SA, Pessu PO, Agoda S, Isong IU, Ikotun I (2011). The concepts and problems of post–harvest food losses in perishable crops. Afr J Food Sci. 5(11):603–613.

Ayo EM, Matemu A, Laswai GH, Kimanya ME (2018). Socioeconomic characteristics influencing level of awareness of aflatoxin contamination of feeds among livestock farmers in meru district of Tanzania. Scientifica. 2018.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Azahar H, Ariff A, Hartini Z (2004). A visual analysis of packaging and labelling design of traditional snack foods in context of malay sme in malacca.

Bashir K (2012). Physio-chemical and sensory characteristics of pasta fortified with chickpea flour and defatted soy flour. IOSR J Environ Sci Toxicol Food Technol.1(5):34–39.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Batt CA (2016). Food Safety Assurance. Reference Module in Food Science.

Carrasco E, Morales-Rueda A, García-Gimeno RM (2012). Cross-contamination and recontamination by Salmonella in foods: A review. Food Res Int. 45(2): 545-556.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chijoriga ZE (2017). Quality and safety of peanut butter processed by small and medium enterprises in Dar es salaam region. (Doctoral dissertation, Sokoine University of Agriculture).

Claval P, Jourdain-Annequin C (2018). The dynamics of Mediterranean food cultures in periods of globalization. AJMS. 4(3): 225-241.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Djukic D, Moracanin SV, Milijasevic M, Babic J, Memisi N, et al. (2016). Food safety and food sanitation. JHED. 14:25–31.

Duan J, Zhao Y, Daeschel M (2011). Ensuring Food Safety in Specialty Foods Production.

Dudeja P, Singh A (2017). Food safety from farm-to-fork-food-safety issues related to processing. In Food Safety in the 21st Century (pp. 203-216). Academic Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ebert M (2017). Hygiene principles to avoid contamination/cross-contamination in the kitchen and during food processing. In Staphylococcus aureus (pp. 217-234). Academic Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fritz M & Schiefer G (2009). Tracking, tracing, and business process interests in food commodities: A multi-level decision complexity. Int J Prod Econ. 117(2): 317-329.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Georgiadis P, Vlachos D, Iakovou E (2005). A system dynamics modeling framework for the strategic supply chain management of food chains. J Food Eng. 70(3):351–364.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Giannetti V, Boccacci MM, Marini F, Biancolillo A (2021). Effects of thermal treatments on durum wheat pasta flavour during production process: A modelling approach to provide added-value to pasta dried at low temperatures. Talanta. 225:121955.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hassan JK, Fweja LWT (2020). Food hygienic practices and safety measures among street food vendors in Zanzibar Urban District. EFood.1 (4):332-338.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Holah JT (2014). Cleaning and disinfection practices in food processing. Hygiene in food processing. 259-304.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hossain MS, Santhanam A, Norulaini NN & Omar AM (2011). Clinical solid waste management practices and its impact on human health and environment–A review. Waste management. 31(4):754-766.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ilhan I, Turan D, Gibson I, ten Klooster R (2021). Understanding the factors affecting the seal integrity in heat sealed flexible food packages: A review. Packag Technol Sci. 34(6):321–337.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jackson LS, Al-Taher FM, Moorman M, DeVries JW, Tippett R, et al. (2008). Cleaning and other control and validation strategies to prevent allergen cross-contact in food-processing operations. JFP. 71(2):445–458.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Meeting. (2016). Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants: eightieth report of the joint FAO/WHO expert committee on food additives (Vol. 80). World Health Organization.

Jolly CM, Bayard B, Awuah RT, Fialor SC, Williams JT (2009). Examining the structure of awareness and perceptions of groundnut aflatoxin among Ghanaian health and agricultural professionals and its influence on their actions. J Soc Econ. 38(2):280–287.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kamala A, Kimanya M, Haesaert G, Tiisekwa B, Madege R, et al.(2016). Local post-harvest practices associated with aflatoxin and fumonisin contamination of maize in three agro ecological zones of Tanzania. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 33(3), 551-559.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kamboj S, Gupta N, Bandral JD, Gandotra G, Anjum N (2020). Food safety and hygiene: A review. Int J Chem Stud. 8(2): 358–368.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kimario ME, Moshi AP, Ndossi HP, Kiwango PA, Shirima GG, et al. (2022). Smallholder farmers storage practices and awareness on aflatoxin contamination of cereals and oilseeds in Chamwino, Dodoma, Tanzania. JCO. 13(1):13-23.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kitigwa SJ, Kimaro EG, Nagagi YP, Kussaga JB, Suleiman RA, et al. (2023). Occurrence and associated risk factors of aflatoxin contamination in animal feeds and raw milk from three agroecological zones of Tanzania. 16(2):149–163.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kothari CR (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International.

Kussaga JB, Luning PA, Tiisekwa BP, Jacxsens L (2014). Challenges in performance of food safety management systems: A case of fish processing companies in Tanzania. J Food Prot. 77(4):621-630.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kussaga JB, Luning PA, Tiisekwa BP, Jacxsens L (2015). Current performance of food safety management systems of dairy processing companies in Tanzania. Int J Dairy Technol. 68(2):227-252.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Loewe M, Al-Ayouty I, Altpeter A, Borbein L, Chantelauze M, e al. (2013). Which factors determine the upgrading of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)? The case of Egypt. The Case of Egypt (July 01, 2013).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Magembe KS, Mwatawala MW, Mamiro DP, Chingonikaya EE (2016). Assessment of awareness of mycotoxins infections in stored maize (Zea mays L.) and groundnut (arachis hypogea l.) in Kilosa district, Tanzania. Int J Food Contam. 3(1):1-8.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Massomo SM (2020). Aspergillus flavus and aflatoxin contamination in the maize value chain and what needs to be done in Tanzania. Scientific African. 10:e00606.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Masunzu N (2017). Safety and quality of commercial cereal-based complementary foods produced and marketed in Mwanza region.

Matumba L, Van Poucke C, Njumbe Ediage E, Jacobs B & De Saeger S (2015). Effectiveness of hand sorting, flotation/washing, dehulling and combinations thereof on the decontamination of mycotoxin-contaminated white maize. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A. 32(6):960-969.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Messer KD, Costanigro M, Kaiser HM (2017). Labeling food processes: The good, the bad and the ugly. AEPP. 39(3):407–427.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Møretrø T& Langsrud S (2017). Residential Bacteria on Surfaces in the Food Industry and Their Implications for Food Safety and Quality. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 16(5):1022–1041.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nakavuma JL, Kirabo A, Bogere P, Nabulime MM, Kaaya AN, et al. (2020). Awareness of mycotoxins and occurrence of aflatoxins in poultry feeds and feed ingredients in selected regions of Uganda. Int J Food Contam. 7(1):1–10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ngoma SJ, Kimanya M, Tiisekwa B (2017). Perception and attitude of parents towards aflatoxins contamination in complementary foods and its management in central Tanzania. J Middle East North Afr Sci.3(3): 6–21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nishimwe K, Bowers E, Ayabagabo JD, Habimana R, Mutiga S, et al. (2019). Assessment of aflatoxin and fumonisin contamination and associated risk factors in feed and feed ingredients in Rwanda. Toxins. 11(5):1–15.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Okpala COR & Korzeniowska M (2023). Understanding the relevance of quality management in agro-food product industry: from ethical considerations to assuring food hygiene quality safety standards and its associated processes. Food Rev Int. 39(4): 1879–1952.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Osei TB & Anfu PO (2019). Evaluation of the food safety and quality management systems of the cottage food manufacturing industry in Ghana. Food Control.101:24–28.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Quinn MM, Henneberger PK, Braun B, Delclos GL, Fagan K, et al. (2015). Cleaning and disinfecting environmental surfaces in health care: Toward an integrated framework for infection and occupational illness prevention. Am J Infect Control. 43(5): 424–434.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rabia AR, Kimera SI, Wambura PN, Mdegela RH, Misinzo G, et al. (2017). Knowledge, attitude and practices on handling, processing and consumption of marine foods in Zanzibar, Tanzania.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ruteri JM (2009). Supply Chain Management and Challenges Facing the Food Industry Sector in Tanzania. Int J Bus Manag. 4(12):70-80.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sasongko SB, Rini BP, Maehiroh H, Utari FD, Djaeni M (2021). The Effect of Temperature on Vermicelli Drying under Dehumidified Air. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 1053(1):012102.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sicignano A, Di Monaco R, Masi P, Cavella S (2015). From raw material to dish: Pasta quality step by step. J Sci Food Agric, 95(13), 2579-2587.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sousa CPD (2008). The Impact of Food Manufacturing Practices on Food borne Diseases. Braz Arch Biol Technol.51:615–623.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Todd ECD, Michaels BS, Greig JD, Smith D, Bartleson CA (2010). Outbreaks where food workers have been implicated in the spread of foodborne disease. Part 8. Gloves as barriers to prevent contamination of food by workers. JFP. 73(9):1762–1773.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tolmacheva T, Toshev A, Androsova N (2019). Methods for ensuring the quality and safety of raw materials used in food for athletes. In 4th International Conference on Innovations in Sports, Tourism and Instructional Science (ICISTIS 2019) (pp. 270-274). Atlantis Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Unnevehr L & Grace D (2013). Aflatoxins: Finding solutions for improved food safety. (Vol. 20). Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

Varzakas T (2016). Quality and safety aspects of cereals (Wheat) and their products. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 56(15): 2495–2510.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vasconcellos JA (2003). Quality assurance for the food industry: A practical approach. CRC press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Waliyar F, Osiru M, Siambi M, Chinymunyamu B (2010). assessing occurrence and distribution of aflatoxins in Malawi.

Walke M, Mtimet N, Baker D, Lindahl JF, Hartmann M, et al.(2014). Kenyan perceptions of aflatoxin: An analysis of raw milk consumption.

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO. (2023). General principles of food hygiene.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zambrano MV, Dutta B, Mercer DG, MacLean HL, Touchie MF (2019). Assessment of moisture content measurement methods of dried food products in small-scale operations in developing countries: A review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 88: 484-496.